Since independence nearly 60 years ago, only two Kenyan communities, the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin, have held the national presidency, which is the highest office in the land.

Founding leader Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, started out as the Prime Minister at independence from British colonial rule in 1963, becoming the President a year later. This happened on December 12, 1964.

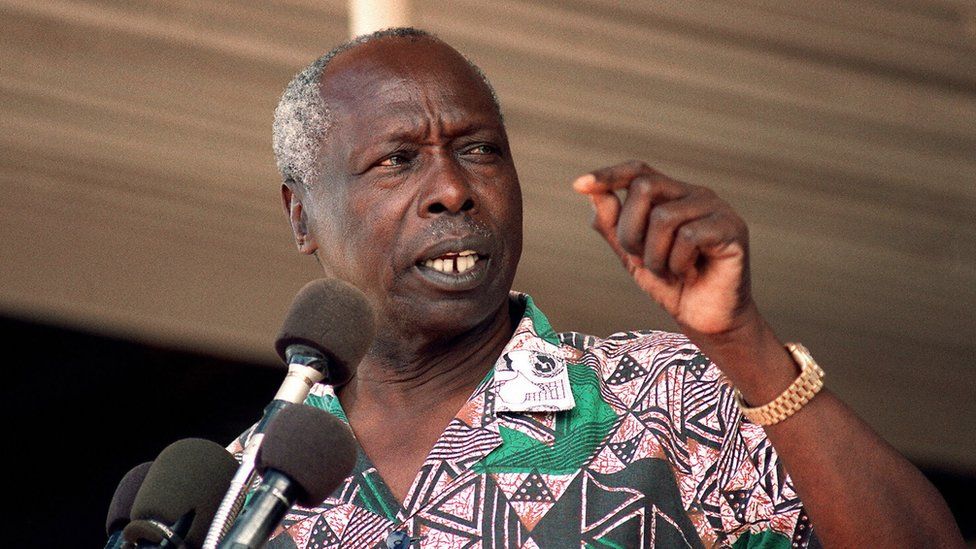

He would remain at the helm until he died peacefully in office in 1978. His Vice-President of many years, Daniel arap Moi, a Kalenjin, ruled from then until 2002, clocking a massive 24 years of unbridled power and privilege for this community.

Its members occupied not just most of the key government and other positions, but also grabbed a chunk of the goodies that came courtesy of one of their own wielding state power.

Then came the gentleman of Kenyan politics, Mwai Kibaki, who led the National Rainbow Coalition (Narc) in 2002, to oust Kanu. He became the President, engineering economic prosperity. In 2013, he passed on the baton to another Kikuyu, Uhuru Kenyatta.

The son of the founding father of the nation has completed his 10 years at the prime location in the capital, Nairobi, State House, and now, power passes back to the Kalenjin community, with William Ruto set to be sworn into office on September 13.

Rigathi Gachagua

Barring a miracle, as he takes charge of the state machinery, he will serve his mandatory two five-year terms. His most likely successor in 2032, will be his Deputy, Rigathi Gachagua, a Kikuyu.

The proponents of the one-man one vote mantra may frown upon this, arguing that it is the winner, irrespective of his or her community, who should hold the highest office in the land. But it is not that simple. There is palpable resentment in the other communities that feel shortchanged.

They had hoped that Azimio flag bearer Raila Odinga, a Luo, would break the monopoly of the populous Kikuyu-Kalenjin in the August 9 presidential election. It never came to pass.

The presidency is at centre of the control of resources. The civil service, which is a major employer, has over the years been dominated by the community whose member wields the presidential power. It is not going to change. The other major community, the Luhya, has only held the vice-presidency.

Musalia Mudavadi, the current ANC party leader and Kenya Kwanza Alliance principal, served under President Moi for several weeks and the only other holder was Moody Awori, who was Kibaki’s Vice-President.

The Kamba had Kalonzo Musyoka an Azimio coalition principal, as the Vice-President of Kibaki.

The bitterness against Kikuyu-Kalenjin hegemony runs deep, considering that Kenya has more than 40 communities. At the current way of doing things, some communities and regions should forget about ever enjoying that top position. This is a matter that always sparks emotional debate.

Speaking at Mudavadi’s mother’s funeral in Vihiga County in January 2011, President Uhuru Kenyatta brought up the issue. He then hinted at the possibility of backing someone out of the Kikuyu and Kalenjin communities, as his possible successor. He later did by throwing his weight behind Raila in the August 9, 2022 General Election.

Responding to another speaker at the funeral, President Kenyatta had said: “…there are two communities that have ruled this nation, maybe it is time to give a chance to other tribes to lead because they also have people.”

This matter has been at the centre of public debate and academic research. In 2011, the Institute for Democracy and Leadership in Africa and other civil society groups in Kenya, unsuccessfully launched a signature collection campaign to petition Parliament to change the Constitution and allow for a rotational presidency.

Post-election violence

The petition was based on research, which established that a majority of Kenyans prefer a rotational presidency. This, they see as the best way to bring about national political stability, and this was fuelled by the horrific experience of the bloodletting in the 2007 post-election violence.

Some 1,500 Kenyans were slaughtered by goons and hirelings of politicians, and several hundred thousand others evicted from their homes and farms, especially the Rift Valley, which was the epicentre of the mayhem.

The European nation of Switzerland, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, has always been touted as having a practical solution to this political nightmare. Switzerland, which is reputed for its political and social stability, thrives, thanks to what is known as its rotational presidency.

Part of that stability comes from the way in which the country is governed. Swiss politics is unlike that of any other nation. While most countries have a single president or prime minister, who sets policies and takes responsibility for decisions, the Swiss don’t.

Members of a seven-member strong Federal Council make decisions jointly and even take turns to be president. While other developed countries, including Germany, have had several leaders in many years, Switzerland has had nearly 20. The Swiss system has served the country well since the 1890s.

Free, fair and transparent elections are at the core of a truly democratic system, but this can only be enhanced by inclusivity that breaks the stranglehold on national leadership by a few communities.